There are a few different ways to construct the headstock area of a neck, both with and without scarf joints. In this post we will explain the different varieties and the pros and cons of each.

Non-jointed Headstocks

Straight One Piece Headstocks

One of the most recognisable headstock constructions. Fender, for example, use one piece of flat wood for the neck and the headstock. The neck wood simply continues straight past the nut with no angle to form the headstock.

Pros:

Strength, because there is no angle the same grain that runs through the neck runs straight through the headstock, giving the headstock strength. For the headstock to break during a fall the break would have to go across the grain, which is much harder than splitting along the grain.

Cheaper, not having a one piece angled headstock dramatically reduces the thickness of wood needed to make the neck. It is said Leo Fender chose this design so the entire neck could be made from a 25.4 mm (1 inch) piece of flat sawn maple. Thinner neck wood should be cheaper and easier to get hold of for most builders.

Wood quality, by using thinner pieces of wood it should be easier to find perfectly quarter sawn or flat sawn wood with straight grain through the length of the neck with no run out. This can be made even easier by making the neck from three pieces of wood just over 19 mm (0.75 inch) wide and laminating them together.

Cons:

Nut break angle, by not having a headstock angle the strings take an almost straight path from the nut to the tuning post, they do not angle downwards. The result is less string pressure on the nut which means the strings can pop out of their nut slot easier during playing.

This has traditionally been solved by adding string trees to the headstock. These bent pieces of metal hold the strings close to the headstock to increase the downwards angle the string takes from the nut. Unfortunately they introduce friction and can pinch the string during bending, stopping it from returning to the correct pitch which puts the guitar out of tune. The friction problem has been helped a lot by the introduction of roller string trees and Graphtech Tusq style string trees which are made of very slippery materials to reduce friction.

Perhaps the best solution to the angle is the introduction of staggered tuners. These are machine heads with the posts that hold the strings getting shorter the further away from the nut. Not only do they increase the break angle over standard tuners, they don’t introduce any extra friction from string trees. You can replace almost any standard tuners with aftermarket staggered tuners but you will have to check the string posts are low enough to eliminate string trees on your guitar.

Angled Non-jointed Headstock

Another very recognisable headstock construction. The neck wood continues past the nut and the headstock is angled back from the nut, with angles ranging greatly from 4-17 degrees. Lower angles result in a lower nut tension and stronger headstock (see Straight Fender style headstocks). Greater angles offer a greater nut tension and weaker headstock.

Pros:

Nut break angle, angled headstocks ensure the strings are angled downwards from the nut to the tuning post, and so they are less likely to come out of the nut slot during playing.

Cons:

Potentially weak, by having a headstock angle, the straight grain that runs through the neck runs past the nut and so there’s a very short section through the headstock before it runs out the headstock face. As you travel further down the headstock face there is no grain left from the neck, it is in the headstock only. This area of short grain in the same direction as the neck, but not connected to it, is a weak point in the headstock. The steeper the headstock angle the shorter the grain and the weaker it is. This is made worse by large truss rod access routes at the headstock.

Headstocks can be made stronger by the addition of a volute. The neck wood is left thicker at the nut and carved either side to form a peak coming out the back of the neck with smooth transitions into the neck and headstock. Placed and carved well the volute should not impact playing. Volutes are standard issue on many brands mid-high end guitars with angled headstocks, e.g. Ibanez, ESP, Schecter, Carvin.

Expensive/wasteful, to the average luthier or hobby guitar builder the thicker wood needed to build a neck with an angled headstock is an additional expense. The additional wood thickness between the headstock and the heel is also mostly cut away, creating waste.

Scarf Jointed Headstocks

What is a scarf joint?

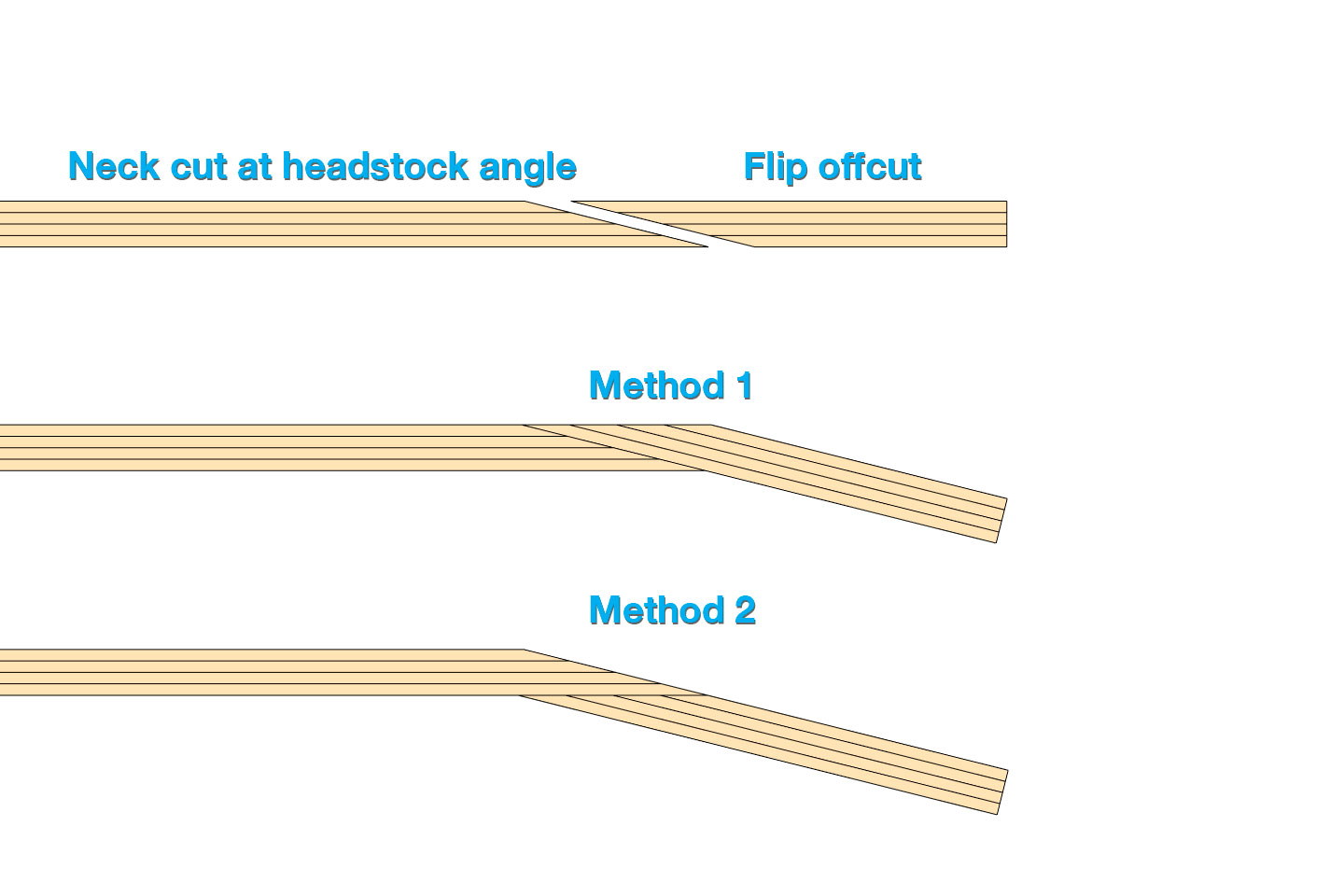

A scarf joint is an angled joint between the neck and the headstock. A cut is made through the neck blank at the desired headstock angle and the off cut forms the headstock. The headstock portion can be glued on in two different ways which we will show below and discuss the pros and cons of both.

Scarf Method One (Headstock Is Made from One Piece)

The headstock is made from one piece and extends past the nut and the fretboard is glued over it. This is the most common method found on production electric guitars.

Pros:

Strength, scarf joints are the strongest method of angling headstock, and with this method of gluing, the headstock is made entirely of wood that’s grain is in the same direction as the headstock; similar to the strength of the Fender style non-angled headstock. Furthermore because the joint is in the neck portion of the wood and not the thinnest part of the headstock (where breaks normally occur), and is also reinforced by the fretboard being glued over it, this is probably the stronger of the two scarf methods; discounting any reinforcement from veneers and headstock ears.

Nut break angle, see angled non-jointed headstock.

Cheaper, the headstock is cut from the same piece of wood as the neck (or can be a completely separate off cut) and so the overall wood needed is much thinner; see straight one piece headstocks.

Wood quality, see straight one piece headstocks.

Cons:

Potential buzzing, if anything in the joint were to move it could affect the fretboard and therefore the action of the guitar. There is anecdotal evidence of buzzing occurring at the 1st or 2nd frets on neck with these scarf joints, but it could be down to the quality of the joint or the conditions of storage (lent against a wall putting pressure on the joint, near a radiator, etc.). Scarf joints have been around long enough with very few complaints so they certainly don’t automatically equal fret buzz.

Time, there are extra steps involved in constructing the joint, and it’s a skilled job that needs to be done well to be strong and have a long life. That said, the individual steps are technically no more difficult than cutting the correct angle in a non-jointed headstock, or gluing on a fretboard.

Scarf Method Two (Headstock Is Made from Two Pieces)

In this joint the off cut is glued to the bottom of the neck blank, and the joint normally lies entirely on the headstock side of the nut. The steeper the headstock angle and the thicker the headstock, the closer the joint will be to the nut. This joint seems to be more common on acoustic guitars rather than electric.

Pros:

Strength, you get the same benefit of better grain direction as method one but as it’s glued to the bottom of the neck it isn’t supported by the neck or reinforced by the fretboard and so isn’t as strong.

You can easily reinforce this headstock by adding at least a face plate veneer, which also hides the joint from the front of headstock. To further reinforce and hide the joint an additional back strap veneer can be glued to the back of the headstock.

On larger 3x3 paddle style headstocks you can completely enclose the joint by adding headstock ears each side of the nut to completely hide the joint from view.

Nut break angle, see scarf method one or angled non-jointed headstock.

Cheaper, see scarf method one or straight one piece headstocks.

Wood quality, see scarf method one or straight one piece headstocks.

Cons:

Time, see scarf method one.

Closing

Scarf joints are fairly rare in mid to high end electric guitars from the big brands, presumably they have all decided buying thick enough wood for angled headstocks is cheaper than the labour cost of the extra steps involved with scarf joints. Fender, Gibson, PRS, Ibanez, ESP and Schecter all use non scarfed headstocks for the majority of their range, with Jackson being the main exception. Scarf joints are fairly common on low end models and budget brands, and also on a variety of acoustic guitars.

Hopefully you can now choose a headstock type for your own build based on the pros and cons and the availability of raw materials in your area. If they are all built to a high standard there is no best option and you can choose another version on your next guitar.